Oxford and the miracle cure - Fleming, penicillin and the drug from the other side

As I explain in my chapter on the drug in The Intelligence Zone, penicillin is profoundly important in the human story.

There are two museums related to penicillin, one in London and one in Oxford. I'll come back to the latter – which is not only a wonderful place, but free to visit - in my next blog. They can both be found from the museums page of this web site – as can many other museums that have helped me in my researches.

The London museum is the Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum and is in Praed Street, near Paddington. As per its title, it is in the laboratory at St Mary's Hospital where Fleming first noted the ability of penicillin to kill off other bacteria. At the time of writing, entry is £4.

Fleming was a man with a mission. That mission was to wage war on the diseases that prey on men – and women. And that mission (as were many of the incredible inventions, discoveries and advances made in the area that my book is about), was fuelled by war. In his case, it was a reaction to his own experiences in the First World War.

Battlefield casualties in WW1 were horrendous. At that time doctors/surgeons treated open wounds with chemical antiseptics – because that was the best they had. However, these were, Fleming believed (and later proved) worse than useless for the job; more likely to kill the body's own defensive cells than the attacking bacteria. Men rotted away. Fleming had observed this from personal experience, having served as a doctor with the Royal Army Medical Corps in France. He subsequently dedicated much of his life to finding something better.

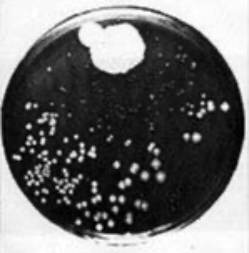

Fleming made two great discoveries; the second of which in 1928, at St Mary’s Hospital in London, was perhaps the most important in the history of medicine. He saw that a growth on one of his culture dishes was killing off the other growths around it. The growth was penicillin.

Professor Alexander Fleming, holder of the Chair of Bacteriology at London University. Image IWM, TR 1468

His growth and identification of the mould, penicillin - the first identified antibiotic – changed the world. It would – and still does – save the health and lives of millions. However, Doctor Fleming could only manufacture the drug in infinitesimal amounts, so it was practically useless. It would have to wait a further ten years before the drug was manufactured in quantity. Given what we know now, this long gap may seem amazing. One reason for it was that Fleming's result, although genuine, was all but impossible to replicate. Why this was so, how to do so, and what the benefits would be for humanity, would only be solved by a team at Oxford University.

That is why Fleming was only one of the three people who received the Nobel Prize for the wonder drug. The other two were Howard Florey and Ernst Chain – who, at Oxford, identified the drug's properties, purified it and began its large scale manufacture. The Oxford story is too big for me to précis here, so you will have to wait until my next post.

The Fleming story is well known, of course. It is so important that, hopefully, you were taught it at school. Before you leave me, though, I would like to tell you about someone else who was following a very similar course to Alexander Fleming and who would, like the Scottish doctor, end up with the Nobel prize. You won't have heard of him; but I think you'll find him interesting.

The one you've never heard of

This man was a Nobel Prize winner, too and in the same category as Fleming (Physiology or Medicine). His name was Gerhard Domagk and he, like many Nobel Prize winners at the time, was a German.

Between the wars the three countries who won the most Nobel prizes for science were Germany (with 20), Britain (with 14) and the United States (who had 10).

Gerhard Domagk started the war of 1914-1918 as an infantryman, fighting the British in Flanders, on the other side of the lines from Fleming. In those battles, 11 of the 15 schoolmates with whom Herr Domagk had joined the German army were killed.

In May 1915, he went to the eastern front as a medic. He recalled the horrors and suffering, especially of infections, at the battlefields, saying:

"There horrible impressions kept pursuing me during my whole life, and made me think how I could take measures against bacteria... I then swore, in case I would return to my home alive, to work and work to make a small contribution to solve that problem.”

Domagk developed a drug which he called Prontosil. He tested the drug close to home, proving it on his own daughter, the six-year-old Hildegarde. She, poor kid, injured herself with a stitching needle while making Christmas decorations in December 1935. She fell on the stairs and stabbed her hand with the needle, which stuck in her wrist. The needle was removed at a hospital. However, Hildegarde developed severe inflammation and fever. After making 14 incisions, the physician suggested that the only way to save Hildegarde was to cut off her arm. Her dad demurred. As Gerhard Domagk later said:

“I asked permission of the treating surgeon to use Prontosil, after I had established by culture that streptococci were the cause of the illness.”

Permission was given. Hildegarde recovered following the Prontosil treatment and her arm was saved.

Domagk and Fleming, two 'enemies' one mission. They were both key players in a sub-plot of astonishing irony, which I will return to in my next blog on the wonder drug, penicillin.

©Alan Biggins March 2024

ps There are a lot more blogs; and a lot more about me, my books and the museums which have helped me on this website. If you want to know more about my books and how they are regarded, follow the link to Amazon here

Create Your Own Website With Webador